Edvard Munch | Graphic Works from The Gundersen Collection

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is renowned for his preoccupation with universal emotions such as isolation, melancholy, anxiety, and love. His graphic works are amongst his most arresting and poignant and are celebrated world-wide for their technical mastery and visual intensity.

The core of this exhibition featured an outstanding group of fifty works on paper by Munch held in a private Norwegian collection, the first time they were exhibited in the UK. Featuring rare, hand-coloured versions of iconic images such as The Scream, Anxiety and Madonna, the show explored Munch’s rigorous experimentation as he revisited subjects to heighten their emotive impact.

The Show

During his long career the celebrated Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) made several thousand prints. The core of this exhibition comprises fifty lithographs and woodcuts owned by a private Norwegian collector, Pål Georg Gundersen, along with additional works on loan to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art from two other private collectors. Including multiple versions of many works, the exhibition underscores the importance of Munch’s serial approach in which he revisited subjects over time, experimenting and reworking images to vary and even transform their emotive impact.

Primarily focused around the period 1895 to 1902, the Gundersen Collection features several unique, hand-coloured impressions by the artist, including a rare version of one of his most iconic works, The Scream. This was one of the images that formed the artist’s Frieze of Life series which Munch described as ‘a poem of life, love and death’. Munch aimed to reveal the psychological and emotional life of man, drawing on his own, frequently troubled experiences to fuel his artistic output. Rejecting Realism in favour of symbolist and expressionist styles, he stated, ‘No longer will interiors and people reading and women knitting be painted. There shall be living people who breathe and feel and suffer and love’.

Munch and Printmaking

Munch first lived in Paris in 1889, and made his earliest prints in 1894 while residing in Berlin. This was a moment of resurgence for the graphic arts in Europe, and in both cities Munch saw the work of leading European artists. In Germany, etchings by Max Klinger and lithographs by Max Liebermann were highly acclaimed, while in France, artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Gauguin were using lithography and woodcut respectively in new ways.

Image Courtesy the Gundersun Collection

For Munch, printmaking was a means to disseminate his work to a wider public, and there were commercial incentives to produce multiple and affordable versions of his increasingly famous images. However, the capacity to create several impressions at a time also allowed Munch to innovate. He frequently returned to images produced months or years previously, and this process of revisiting themes singles Munch out. In 1935, he wrote: ‘I have constantly worked further on my prints and experimented with different impressions – I often used prints as a means of drawing and hand colouring.’ As well as applying ink or paint by hand after printing to make individualised works, Munch altered colour schemes, varied the weight, colour and texture of his paper, and experimented with, and blended different printing methods.

The Modern Life of the Soul

Munch suffered from serious childhood illness and continued to be plagued by both ill-health and depression during his adult life. ‘I have been given a unique role to play on this earth’, he wrote, ‘… given to me by a life filled with sickness, ill-starred circumstances and my profession as an artist. It is a life that contains nothing even resembling happiness.’ His introversion and preoccupation with mortality is often apparent in his confessional self-portraits. This is particularly true of his first self-portrait print, made in 1895, aged just 32 years old, in which he included a skeleton arm that acts as a momento mori (reminder of death).

Image Courtesy the Gundersun Collection

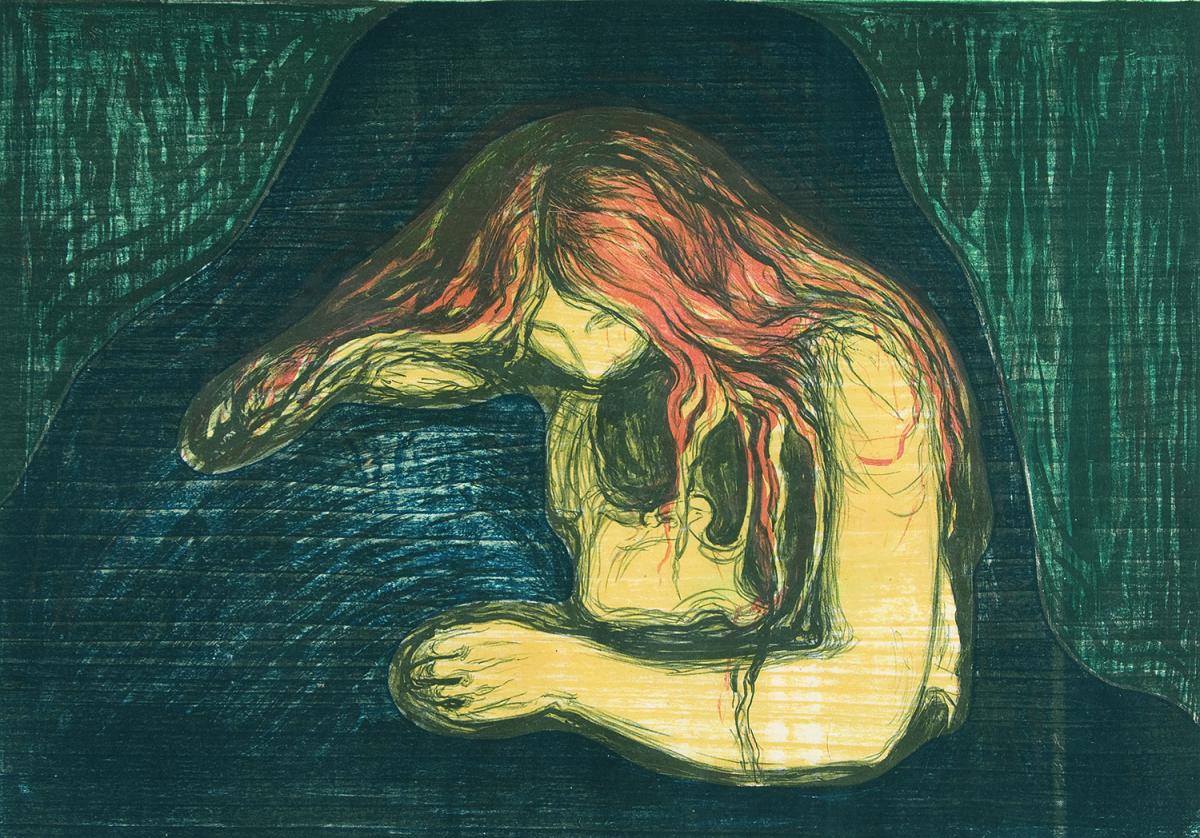

Though Munch never married, women, love and the relationship between woman and man are recurring themes in his work. Female figures appear in many guises: from sister and mother to lover and seductress. Munch made portraits of women he knew personally, such as Eva Mudocci as well as using professional models, and frequently, his depictions of women are highly symbolic, as is seen in Woman in Three Stages. In his images of couples, the line between attraction and repulsion often appears ambiguous. Conflicting emotions suggested in works such as Vampire reflect Munch’s unease about the duality of man’s relationship to woman, in which man longs to abandon himself to love, but fears losing control.

Image courtesy the Gundersun Collection

Anxiety of Life and Death

While death was a common theme for Symbolist artists during the late nineteenth century, Munch’s tragic family history lent the subject a deeply personal resonance for the artist. By the age of thirty-two, four close family members had died and in his journal Munch noted that ‘illness and madness and death were the black angels that stood at my cradle’. In particular, the premature death of his favourite sister Sophie, when she was fifteen years old, affected Munch profoundly, and drove him to produce an extraordinary body of paintings and prints that show his sister on her sick-bed. Munch considered the lithograph of The Sick Child his most important print, and it is a central image in his series The Frieze of Life.

Image courtesy the Gundersun Collection

Alongside these works, and also forming part of The Frieze of Life, Munch worked on images dealing with existential human angst. These not only reflected his own fragile emotional state, but articulated contemporary unease in the face of modern, and increasingly urban and secular life, ideas that were discussed by the literary circles of which Munch was a part. The most famous of these is The Scream, an image that has become a universal icon.

Image Courtesy the Gundersun Collection

The Lonely Ones

In Munch’s work, human isolation stems from both the anxiety of modern life and the painful experience of lost love, jealousy and abandonment and the artist used the full force of graphic media to express these difficult emotions.

This is particularly evident in his use of woodcut, where he often chose blocks of wood with a pronounced grain to add depth and texture to the image. While in lithographic printmaking the ink used can create soft, sensuous effects, woodcut has a bold, immediate directness. Munch carved his own wooden blocks and developed a technique by which he would cut them to create a jigsaw-like puzzle that once reassembled would allow different colours to be printed simultaneously. He could therefore change the appearance and effect of a work by altering the colour combinations, while simultaneously maintaining the overall composition. In addition to these techniques, the relationship of figure and environment in Munch’s compositions often stresses a sense of loneliness. Even together, the couples in Two Human Beings and Towards the Forest appear alone and adrift against the infinite landscape.

Image courtesy the Gundersun Collection.

Munch and Scotland

The exhibition also includes a small archival display focusing on Munch’s first solo exhibition in the UK that was held in Edinburgh in the winter of 1931-2. The show was organised by the Society of Scottish Artists (SSA), whose aims were to ‘stimulate … younger artists to produce more original and important works, and to procure for its annual exhibition interesting and educative examples of various schools of contemporary art’. Comprising twelve paintings, including figurative compositions and landscapes, it opened as part of the annual SSA exhibition on 28 November 1931. By the time it had closed on 9 January 1932 a debate had been played out in the letters pages of The Scotsman and thanks to the furore, record visitor numbers had been received. Despite the critics, the exhibition provided an opportunity for artists in Scotland to see Munch’s work and his influence has been identified in the work of figures such as William Gilles and William MacTaggart who were inspired by the artist’s expressionist handling of colour and form.

Find out more

Partners

Friends go free

Become a Friend to enjoy unique access to the nation’s art collection with unlimited free entry to exhibitions, Friends-only exhibition previews and a 10% discount in our gallery shops & cafés.

What's on

Browse what's on at the galleries below, or filter results to narrow your search.