Realism

Used generally for art that attempts to represent things as they appear. It specifically refers to a mid-nineteenth century movement in France, led by Gustave Courbet, that rejected the sometimes obscure subject matter of academic painting in favour of more accessible scenes of everyday life.

What is Realism?

Realism is a broad ranging topic that refers to art which represents subjects with close attention to detail, often capturing gritty subjects and the harsh realities of ordinary life. The term is most frequently applied to French Realism, a style of art produced in the mid-nineteenth century that broke with historical and allegorical subjects in favour of real people in ordinary settings.

French Realism and the Revolution

French Realism came to prominence in 1840 and lasted well into the late nineteenth century. The style gained momentum after the French Revolution in 1848, when the monarchy of Louis-Philippe was overturned and the Second Empire was established under Napoleon III.

Throughout society democratic reform was being fought for, a quality that artists yearned to invest in their art. The idealised Classicism and opulence of Romanticism no longer seemed to fit with the social climate and artists increasingly developed Realist styles of painting that reflected the ordinary and the humble. Gustav Courbet wrote in 1861, 'Painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist in the representation of real and existing things.'

Realist painting combined a near photographic level of detail with direct subject matter drawn from ordinary life, such as working people, city streets, cafes and sexualised bodies. They placed great importance on simple, ordinary people, an ethos that was echoed in the literature of Emile Zola, Honore de Balzac and Gustave Flaubert. Their ideas also coincided with the publications of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s socialist philosophies in The Philosophy of Poverty, 1846 and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto of 1848, publications which shed light on marginalised people and their tangible struggles.

French Realist Artists

Gustave Courbet is often regarded as the first Realist painter, directly confronting the traditional history painting that dominated the Paris Salon and the teaching methods at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in favour of gritty, true to life subjects. Amongst his subjects were hard-working people, often portrayed undertaking backbreaking work on a monumental scale, challenging subjects which were frowned upon by the art establishment. When several of his paintings including The Studio, 1854-55 were rejected by the Exposition Universelle of 1855, he set up an independent showcase nearby in a rented space, which he titled Pavillon du Realisme. Alongside the exhibition he produced an accompanying catalogue containing a manifesto for Realism, urging other artists to follow his socialist path.

French painter Edouard Manet also courted controversy, through both subject matter and style. He deliberately rejected the conventions of single point perspective in favour of a natural perspective, with flattened surfaces and large areas of black that were influenced by Japanese prints. His blatant portrayals of female nudes as prostitutes, including Olympia, 1863 and Le Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe, 1863, which was exhibited at the Salon de Refuses, caused provocation amongst gallery going audiences and the press, playing into his hands and garnering him a notorious reputation as an enfant terrible.

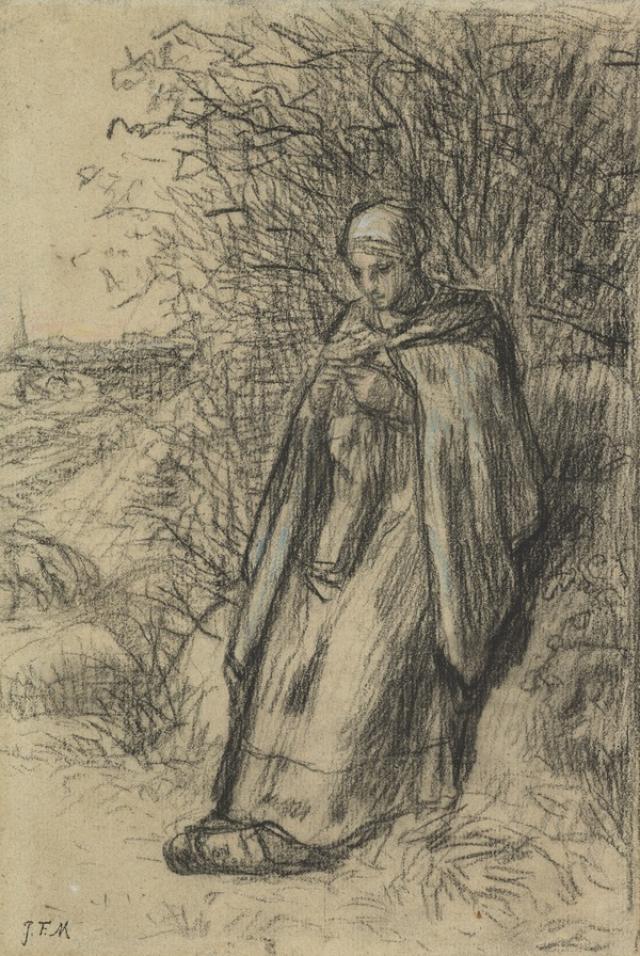

Other progressive Realist artists in France at the time include Jean-Francois Millet, who showed hard-working rural peasant people with great pathos, such as Depart Pour Le Travail (Going to work), 1863. Rosa Bonheur captured working farmhands, and Jules Breton is best known for his sympathetic studies of working women. Jules Bastien-Lepage set a series of paintings in the French rural area of Damvillers, including Pas Meche (Nothing Doing), 1882.

Legacy

The trend for Realist painting that emerged in nineteenth-century France spread throughout Europe and the United States in the following decades. As the style was not instigated by a specific group, it was a widespread phenomenon with far-reaching influences. French Realism is often cited as the bedrock for Impressionism, instigating a general move towards social engagement and the depiction of reality over idealisation, while Courbet and Manet demonstrated an independence of spirit that proved highly influential on generations of Modernist to come; they are often referred to today as the first artists of the avant-garde.

The term Modern Realism refers to art produced after the explosion of abstract art in the twentieth century, such as James Cowie’s detailed portraits, while other variations in the style that have evolved include Social Realism, which emerged predominantly in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, Photorealism, which came out of Europe and America in the 1960s and the more expansive Hyperrealism of the 1970s which included painting and sculpture, epitomised in the startlingly lifelike sculptures of Ron Mueck.