Fresco

Lifted from the Italian word ‘fresco’ (‘fresh’), the term refers to wall paintings generally made on wet plaster so that the coloured pigment is absorbed into the surface of the wall, resulting in brilliant, vibrant colours. Fresco is an ancient tradition of painting that came to prominence during the Italian Renaissance and has been revived by various artists since.

How is a Fresco Made?

Three types of fresco painting have emerged throughout the history of art – buon affresco (true fresco), mezzo fresco (medium fresco) and fresco secco (dry fresco). The first is the most prominent and popular technique, where mineral or earth pigments are applied to a layer of wet lime or gypsum plaster, known as an arricciato, which absorbs the pigment fully as it dries. Artists first sketch out a composition in charcoal and sinopia onto the wet plaster, before applying pigments suspended in water, which unite with the plaster as they dry, resulting in vivid, glowing colours. Only enough wet plaster, known as intonaco, is applied for a day’s work, with any further retouching added later in fresco secco once the surface is dry.

The fresco secco, or dry, technique demands a binding medium, such as glue adhesive or egg yolk to make paint stick to the surface and produces less vibrant colours. Mezzo fresco, by contrast, is made on a nearly dry intonaco and was particularly popular during the Italian Renaissance.

Early Fresco Paintings

Some of the earliest examples of fresco painting have been traced back to 2000 BC, made by Minoans in Crete, Israel and Egypt to adorn palace walls and tombs, while others date from Bronze Age Greece in 1600 BC. Ancient Etruscans and Romans also made frescos, most commonly on the walls of wealthy patron’s tombs, depicting them eating, drinking and enjoying the afterlife.

Ancient Roman examples of fresco paintings depicted false marble walls, columns and balconies, lavishly decorating the homes of those who could not afford such luxuries in real life. In 100 BC frescoes appeared in China during the Han Dynasty, while others have been uncovered on the walls of Hindu temples in India from around 500 AD during the Guptan period, illustrating scenes from Hindu stories. Eastern Orthodox Christian Art in the following centuries often relied on fresco painting to adorn churches and cathedrals, depicting Biblical figures.

Fresco Painting in the Italian Renaissance

During the Italian Renaissance fresco painting came into its own and reached a peak, with many of the finest examples from the period still in excellent condition today. Frescoes from the time illustrated scenes from the Bible or the lives of saints onto walls in public or private buildings and Christian churches. Gold leaf was popular, particularly during the Early Renaissance, lavishly adorning walls with a luxurious metallic sheen, as exemplified in Giotto di Bondone’s Scrovegni Chapel, 1305. Other artists explored the ways fresco painting could add depth and space to their surroundings, such as Fra Angelico’s deeply contemplative scenes at the Dominican Friary of San Marco, 1428, which explored the ways new discoveries in linear perspective could create realistic architectural space with depth, light and shadow.

During the High Renaissance Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci made some of the most famous frescoes in the world. Michelangelo’s hugely ambitious Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508-12, featured over 300 figures from religious scripture and took over four years to complete. As a way of adding extra depth to his figures the artist scraped away some of the wet plaster around their bodies to create lighter, visible ‘outlines’, making them stand out from the background behind them. By the later Renaissance the demanding technicality of fresco painting was eventually superseded by oil painting, first on wooden panels and later onto stretched canvas supports.

The Fresco Revival

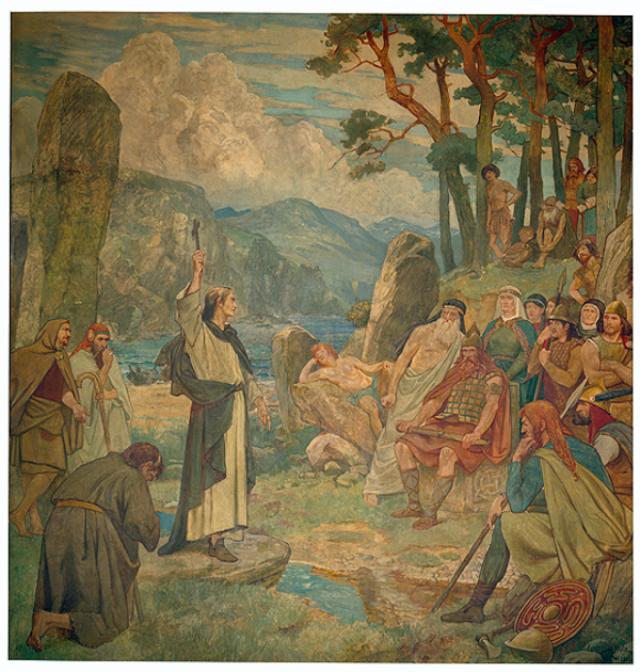

In the nineteenth and twentieth century fresco techniques underwent a revival in Britain, with mural painting in public buildings achieving a newfound popularity, particularly amongst Pre-Raphaelite painters and those associated with The Arts and Crafts Movement, who looked back to earlier, pre-industrial forms of art. In the Scottish National Portrait Gallery English artist William Brassey Hole was commissioned in the late nineteenth century to create a vast series of fresco murals in and around the great hall, including illustrative scenes depicting St Columba bringing Christianity to Scotland, and a Processional Frieze celebrating figures from Scotland’s history. Arts and Crafts pioneer Phoebe Anna Traquair also painted Renaissance style frescoes, including those on the walls of Mansfield Place Church in Edinburgh in the early twentieth century, famously referred to today as ‘Edinburgh’s Sistine Chapel’.

Contemporary Fresco Painting

While fresco painting is less mainstream today, various artists have looked back to the ancient technique with contemporary eyes. Mexican artist Diego Rivera painted a series of murals in the San Fracisco Bay Area, including the iconic Marxist masterpiece The Making of a Fresco, 1931, depicting different layers of society at work on a complex arrangement of scaffolding. American-Italian painter Francesco Clemente has also tapped into the rich history of fresco painting and updated it with contemporary ideas, producing murals such as Avo Ovo, 2005, in Madrid, a richly complex work which reflects on Neapolitan history and interweaves it with the artist’s own personal experiences.