Paintings and sculpture of noteworthy historical events were once considered to be the highest form of artistic expression. Unlike other European nations, Scotland did not have a firm of a tradition of ‘history painting’, mainly due to a complex combination of religious reform, limited patronage (particularly following the 1603 Union of the Crowns), and insufficient artistic teaching. Following the Act of Union in 1707, Scotland sought to carve out an identity that was distinct from England. The beginning of the eighteenth century saw many Scottish artists shifting away from the traditional genres of portraiture and landscape, and looking back to Scotland’s past for inspiration.

Tales of heroic Scottish battles, chivalric Jacobites, and faithful Kings and Queens that are so familiar today were first recorded in an accessible way in books such as William Robertson’s influential History of Scotland (1759), and Gilbert Stuart’s sentimental, albeit, influential work of the same title (1783). This nostalgic celebration of the past was part of a growing national desire to seek out Scotland’s authentic history, and provided rich descriptions for artists who tapped into the growing national desire to create a distinct national identity.

David Wilkie was a pioneer in the interpretation of Scottish history into paint, and laid the foundations for art that illustrated the dramatic past. His contemporary William Craig Shirreff may have reached the same heights but for his untimely death. The favoured subject among artists was consistently the life of Mary Queen of Scots, particularly the versions related by Robertson, Stuart and in Sir Walter Scott’s romantic novels.

Although Mary as a character and the Reformation era was seen as fascinating in the nineteenth century, Wilkie’s early works had inspired artists to look at other historical topics. Popular subjects included the suppression of the Presbyterian Covenanters in the 1680s, and the Jacobite campaigns of 1745-6, but also the heroic as well as the treacherous deeds of individuals.

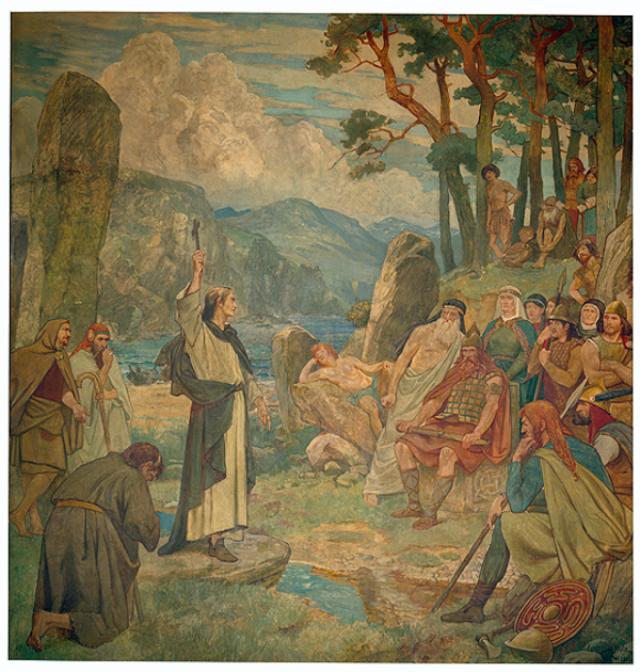

The opening of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 1889 marked the high point in this area, particularly William Brassey Hole’s mural decorations and Processional Frieze showing over a hundred and fifty figures or ‘heroes’ from Scotland’s past. By the end of the nineteenth century, the effects of the Celtic Revival were becoming apparent in Scottish art, with artists looking back to indigenous ‘ancient’ subjects.

During the first years of the twentieth century, artists generally did not engage with episodes from Scottish history. The social and economic turbulence of the inter-war years coincided with the birth of the literary ‘Scottish Renaissance’, which saw writers such as Hugh MacDiarmid seeking to create and define forms of contemporary Scottish literature. Their need to revitalise Scottish art and culture was picked up by other artists such as William Johnstone, who adapted contemporary techniques to respond to his local Scottish environment.

John Bellany’s work built on a number of Scottish traditions, and he is ideologically indebted to the Scottish Renaissance. Following the second World War he produced a number of highly ambitions and personally symbolic paintings which used the traditional Scottish subject of fishing and its associated folklore. Simultaneously, there was a developing Scottish urban aesthetic. Artists not only focused on the social-political aspects of urban life, but also captured some of its horrors, such as Ian Fleming’s painting of the Clyde bombings during the second World War.

The widespread fashion for conceptual, minimalist art that prevailed during the 1970s was a challenge for many Scottish artists. Bellany and Alexander Moffat may be credited as the primary factors in the emergence of the ‘new Glasgow Boys’ of the 1980s, whose work shied away from conceptualism, and created a new mode of representation based on pictorialism, realism, history painting and the figure. Among this group was Peter Howson, who explored Glasgow’s sectarian football violence, Steven Campbell, and Ken Currie, all of whose works engaged strongly with contemporary Scottish culture.