Contrapposto

This term usually refers to a standing human figure carrying its weight on one leg so that the opposite hip rises to produce a relaxed curve in the body, although it can be used more generally to describe any twisted figure. It is associated with Renaissance sculptors who looked back to Ancient Greek and Roman models for inspiration.

Origins of the Term

The Ancient Greeks first invented the Contrapposto stance in the early fifth century BC. It arose as an alternative to Greek Kouros sculptures, where figures are seen front on with even weight on both legs and one foot slightly in front of the other, which had a stiff, rigid quality. One of the earliest examples of the Contrapposto pose can be seen in the ancient Greek sculpture of Dosyphoros (Spear Bearer), made in around 450-440 BC, which revealed how the curved position could lend sculpture a far more natural, lifelike quality. Issues of balance presented technical challenges, which many artists overcame by adding props for figures to lean on. In the following centuries the style continued to prove popular, appearing in both draped and nude figures, but was lost throughout the dark ages.

The Italian Renaissance

During the Italian Renaissance and Mannerist period various artists revived the classical pose, naming it Contrapposto, which they enlivened in painting and sculpture with a greater knowledge of human anatomy. Several depictions of the character David, first by Verrocchio, then Donatello and later Michelangelo reveal an evolution of the Contrapposto style as it became more elaborate, exaggerated and anatomically accurate, culminating in Michelangelo’s iconic High Renaissance sculpture, which combines a flowing s-shaped body with a powerful sense of muscular strength and valour.

Such poses also appeared in Renaissance and Mannerist paintings, where single and multiple figures were given dynamism and energy through twisted poses suggesting movement, as seen in Titian’s coy Venus Rising from the Sea, 1520 and the energised Diana and Callisto, 1556-59 where carefully modelled figures take on a sculptural quality as if moving through the space around them.

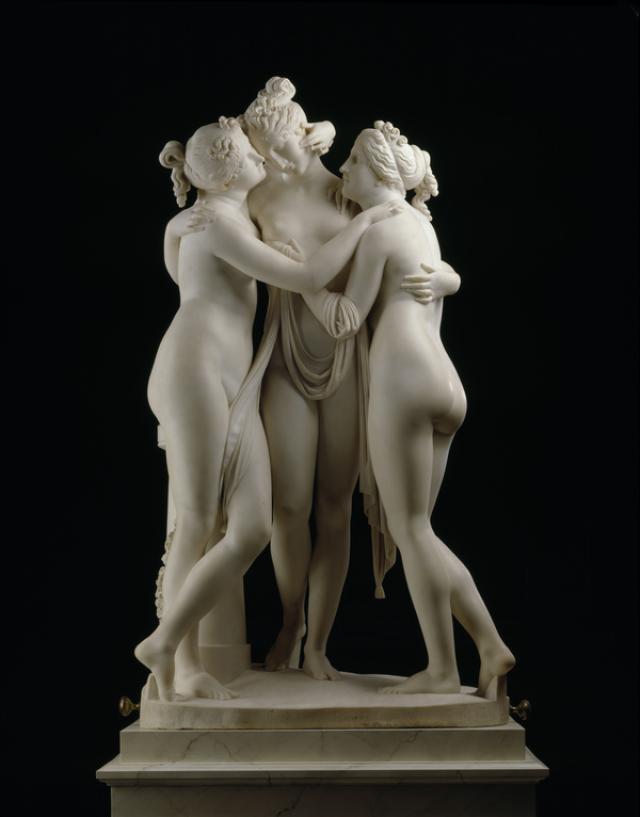

Neoclassical sculpture in the nineteenth century saw a surge of interest in the popular Renaissance trend for Contrapposto bodies, as exemplified in Antonio Canova’s The Three Graces, 1815-17. Canova’s three female muses create a rhythmic sense of movement between their bodies as they almost appear to dance together in harmony, with their free-flowing energy echoed in sinewy hanging drapes.

The Contrapposto Figure in Modern Times

In contemporary art the Contrapposto pose continues to provide an entry point for artists working in a range of media, often with a knowing nod to the age-old tradition. In Bruce Nauman’s performance video art Walk with Contrapposto, 1968, the artist attempts to transverse down a narrow corridor while remaining in the twisted position, creating a pastiche of the supposedly relaxed pose. Many modern and contemporary photographers have also deliberately posed figures in Contrapposto as a playful reference to Mannerist representations of the human body, including Robert Mapplethorpe and Lindsay Key.